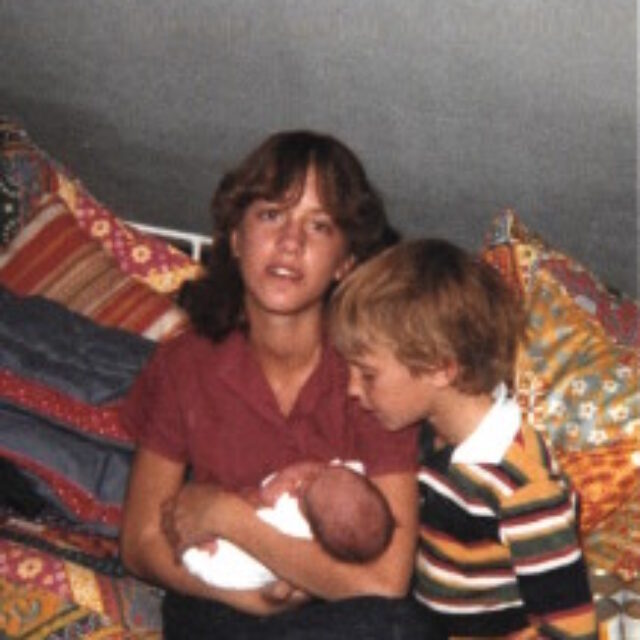

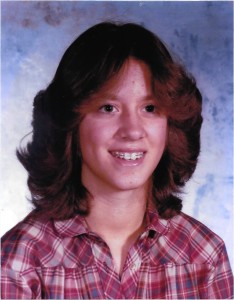

I had my daughter, Stacey, when I was very young – just 19 years old. At 13, Stacey was a sweet, dimpled little girl with an old soul. When we were low on groceries, it was Stacey who would tell me we needed to go to the store. She was caring and big-hearted, often visiting elderly residents in a nearby nursing home who had no visitors. The oldest of three, she took care of her younger brother and sister. And, she loved to bake. In fact, she loved it so much, she even skipped school once so she could bake a cake.

It was May 21, 1980 — a Wednesday and just another normal school day. Stacey was in the 8th grade and her typical after-school routine included picking up her sister, Sarah, from the babysitter’s house on her way home. Sarah was eight months old at the time. That day, I arrived home from work at around 5:30 p.m., but was surprised to find that Stacey and Sarah were not there. The next thing I knew, police officers were at the front door telling me something had happened to Stacey and I needed to come with them. They took me to a home next door to where Stacey had been hanging out with some friends in the neighborhood. In front of a crowd of strangers, I was told Stacey had been shot to death.

Startled and confused, I had a million questions swirling around in my head about how this tragedy could have happened, but I was not allowed to ask them. Later that day, the police told me that Stacey was visiting a boy’s home with two other girlfriends. The boy accessed a loaded shotgun that was hanging on the wall. He pointed the gun at the girls to “scare” them, and pulled the trigger.

Stacey died instantly – her body destroyed by the shotgun blast. I never saw Stacey’s sweet, dimpled face again.

The months that followed were plain torture. I was not allowed to speak to anyone who was there during the shooting. The boy was charged, but he never went to trial – there was only a hearing, which only happened after I pushed for it. The hearing took five minutes and no one said anything to us – no explanation, no apologies. The boy did not serve any time and the shooting was expunged from his record when he turned 21. I never fully blamed the boy. I felt his parents were also responsible because they left a loaded shotgun accessible to children. They were aware of the risks guns posed: their neighbors’ son had shot and paralyzed a woman just months before Stacey was killed.

Our advice to parents who own guns: for the sake of your children and the children who visit your home, please store your guns responsibly. It could mean the difference between life and death.

The lawyers advised us to not file a civil lawsuit. We were told that because Stacey had no income, there was no monetary value to her life.

Stacey died 37 years ago—just after Mother’s Day—and the pain of her dying in such a senseless and preventable way has not subsided. I pressed on because I knew Stacey would have wanted me to take care of her brother and sister and because I wanted to set a good example for my children should they ever face tragedy. But the death of a child changes a person forever. My life has never been— nor will it ever be— the same. It impacts your marriage, your friendships and your sense of security. My son, who was 8-years-old at the time of Stacey’s death, still suffers from anxiety, which I believe is a direct result of the shooting.

Today, our daughter, Sarah, is a passionate advocate for gun safety and educates others about safe and responsible gun storage through Moms Demand Action’s Be SMART program. I am so proud of her and know that she is saving lives.

Our advice to parents who own guns: for the sake of your children and the children who visit your home, please store your guns responsibly – locked, unloaded and separate from ammunition. It could mean the difference between life and death.